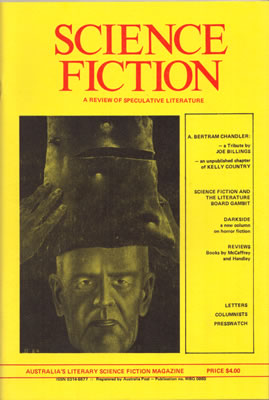

(Cover Nick Stathopoulos)

Science Fiction - A Review of Speculative Fiction - Vol 6 No 3 1984

Short Story

The Penguin is a Flightless Bird

For quite a long while now I’ve been boring the ears off friends and acquaintances in at least six countries with a sort of blow by blow account of the writing of Kelly Country. Now I am saying that there was one year’s research, one years writing, six months during which I was trying to sell the bloody thing and, to date, six months arguing about it, Penguin Books’s editor is one of those who firmly believes that a novel should be the bastard off-spring of the mating of the minds of the editor and the author. (Actually she is a very good editor; one piece of rewriting that I did to her requirements has improved the story no end.)

But she wanted the Battle of Batoche sequence cut out entirely. I stood firm and said that I had promised the late Susan Wood that the Riel Rebellion (a nasty little civil war in Canada that actually happened at the same time as my fictitious Australian War of Independence) would be incorporated in my story. So the Battle of Batoche sequence has stayed in, although it had to be shifted from early in the novel to quite late in the action.

She wanted the real-life Louisa Lawson-who had been dragged in by the hair, kicking and screaming, just to annoy my everloving-purged from the party. But Louisa stayed in.

She wanted the City of Bathurst incident-the sinking of an Australian passenger liner in the Bay of Biscay by a German Zeppelin early in World War I, thus dragging the Australian Republic, hitherto neutral, into that conflict-cut out. I insisted that it be kept in.

She wanted the Battle of Kiel sequence-also World War I-cut. With great reluctance I let her have her way on that one.

Probably most people know by this time what Kelly Country is all about. I used the ideas propounded quite a few years ago by the English mathematician J. W. Dunne in his An Experiment with Time and The Serial Universe. My narrator is sent back in time, into the mind of his great-grandfather, in order to be able to write an eyewitness account of the Siege of Glenrowan, his ancestor having been among those present in Ma Jones’s pub on that occasion. He somehow gets control of great-grandfather’s mind and interferes, stopping Thomas Curnow from flagging down the special train, not realising that by so doing he has shunted history on to another track. (He does realise, of course, when he returns to a somewhat different Here-and-Now.)

The narrator also has a French-Canadian great-grandfather-hence the Battle of Batoche sequence-and a German grandmother, who witnesses, from the ground, the Battle of Kiel.

In the story the Australian Revolution succeeds because the rebels receive considerable outside help, from the USA. The Harp in the South Committee-with Ned Kelly’s famous cousin, Buffalo Bill, as its figurehead-raises money and volunteers. Francis Bannerman-the world’s first international secondhand arms dealer-supplies weaponry. Certain officers of the American army regard the war in Australia as an ideal opportunity for trying out newfangled devices in somebody else’s country.

I didn’t cheat. All of the new-fangled devices were, in the 1880s, already in existence or on the drawing boards. There was the Andrews airship, which flew successfully in 1864. There was the steam-operated Gatling cannon, which Dr Gatling was trying, without success, to peddle to the military. There were the primitive tanks, steam-driven, armoured traction engines with steam-operated Gatlings as their armament. Such things had been considered at that period.

In the novel the success of the Australian Revolution doesn’t affect world history all that much. The First World War happens on time. So does the Russian Revolution. So does the Second World War. And the Vietnam War. There are, however, differences between the two time tracks.

For example, the use of the airship in warfare in the l880s does lead to an accelerated development of lighter-than-air flight. By the time of World War I there are the airship aircraft carriers-an idea that wasn’t played around with until the 1920s in our history. There are Zeppelins armed with cannon rather than machine guns. During our First World War some later German dirigibles, at the finish, did pack quite a wallop but their guns were only 20mm. In Kelly Country Admiral Strasser’s ships are armed with 88-mm cannon.

There was a Strasser in our real history, He held the rank of Fregattenkapitan, equivalent to that of Commander RN. Despite this comparatively low status he was the German Navy’s Zeppelin king. He loved airships but they didn’t love him. Every time that he went on a raiding flight himself everything would go wrong. This was true when he flew in LZ7O, a super-Zeppelin with a very high ceiling and armed with 20-mm cannon, on 5 August 1918. Although Kapitanleutnant (equivalent to Lieutenant, RN) von Lossnitzer was nominally in command, there is little doubt that Strasser himself was in charge of his fine new ship.

She was shot down in flames, by British fighters, with the loss of all hands, She fired only a few ineffectual shots from her 20-mm cannon.

So I decided to give Peter Strasser some posthumous recognition and a long overdue promotion. Following this preamble is the deleted chapter in which this is done.

Edited out of the novel by Penguin Australia (Included in the DAW US edition)

Another breakfast, and this one in real life (but was it?) and not part of a dream. . .

Another breakfast, but with an army mess corporal serving the meal and not a pretty (sometimes) maidservant. Another breakfast, but sitting opposite me a major, more or less in my age group, and not an elderly, retired admiral.

As Admiral Grimes had been in the dream, Major Puffin was reading the Sydney Morning Herald. This morning, however, there was no report of a disaster in the Bay of Biscay. Splashed over the front page were reports of more disasters in Vietnam.

Duffin laid aside the paper, picked up his coffee cup and gulped noisily.

“Wars . . .” he muttered. “Wars. Nothing but wars. Oh, I’m a soldier but I can’t help feeling, now and again, that Australia should have kept out of all these foreign involvements from the very start. The Boer War. The First World War…”

“And the Second World War,” I said.

“That was different, Grimes. The Japanese attacked us, plastering our naval base at Darwin just as they plastered the Yanks at Pearl Harbour.”

“And the Germans,” I said, “in the First World War, attacked City of Bathurst, a neutral ship, in the Bay of Biscay.”

“Oh, yes. That dream of yours that you were mentioning just as we were starting breakfast. It would have been better if you’d actually been there, aboard the ship, instead of reading about it in the morning paper.”

“Better?” I asked. “How so? That was the sort of party that I prefer not to be invited to. Being bombed and machine-gunned in an unarmed ship isn’t my idea of fun,”

“And your great-grandfather, the man whose career you’re supposed to be reliving instead of wandering off to Canada and the Bay of Biscay and the good Lord knows where else... He led the raid on Kiel, didn’t he? It’s a pity that you weren’t there.”

“I couldn’t have been,” I told him. “You know how this Time Travel business works, going back along the World Line, Once great-grandfather had a son he-how shall I put it?-became out of bounds. And I had access to the mind of that son, my grandfather, only until he became a father…’

“And your grandfather wasn’t in the Navy, so he wasn’t at Kiel.”

“Just as well,” I said. “Did you ever make a study of that battle?”

“Not in any great detail,” he said. “The Army historians tend to ignore any fighting that took place in the air or at sea. I could tell you all about the Battle of Berlin. An uncle of mine was a panzer colonel. But Kiel? No.”

“Kiel,” I told him, “was the main base both for the German Navy’s U-Boats and its Zeppelins. Insofar as the submarines were concerned access to the North Sea was either via the Kattegat or the Kiel Canal. It would have been suicidal for Allied surface craft to attempt to run the Kattegat and, of course, the Kiel Canal was out of the question…”

“I don’t suppose that the Allied captains had any German money to pay their canal dues,” said Duffin.

“Very funny. Anyhow, Kiel was bristling with anti-aircraft batteries. Nonetheless it was decided to carry out a large scale bombing attack. The most suitable ships were the Australian dirigibles, the Brennan metalclads. They had a high ceiling for those days. 20,000 feet. They were armed with electrically operated 1’’ Gatlings, with a fantastic rate of fire. Even should German fighter planes succeed in climbing to engage them the Gatlings would make mincemeat of the enemy. And the metal skins of the dirigibles, although not armour, would stop the average German machine-gun bullet. Too, the gas cells were self-sealing. Brennan-he was a very versatile scientist and engineer-as well as being the designer of the ships themselves had also developed the bombs that would be used. The ‘burrowing bombs’. One of these, falling as much as two hundred feet away from one of the canal locks, would cave it in.”

“You seem to have done your homework;’ said Duffin.

“It’s family history,” I told him. “And, as you know, I am something of an historian. For a while I’ve been toying with the idea of writing a novel set during World War I, I’ve done plenty of reading up—including Luft Admiral Strasser’s memoirs.

“Strasser was as devoted an airshipman as my great-grandfather. It was Strasser who was responsible for the development of the recoilless 88-mm cannon. At the time that the Allies mounted the raid on Kiel four Zeppelins were so armed—LZ70, LZ71, LZ72 and LZ73. Like the Brennan metalclads these dirigibles had a high ceiling. The other ships, older and smaller, could clamber as high as 15,000 feet. These had only a few machine guns for their own protection but each carried at least a dozen fighter aeroplanes.

“The night of the raid was brightly moonlit, with a clear sky. The wind over the North Sea was easterly, at about ten knots. The Allied air fleet lifted from the Royal Navy’s Airship Base at Pulham, in East Anglia. There were twenty Australian metalclads, with the flagship, Deirdre, in the van. There were ten French semi-rigids. My understanding is that these ships were among those present despite my great-grandfather’s lack of confidence in them. There were ten Royal Navy airships of essentially Zeppelin design. Finally there were ten of the Royal Navy’s airship aircraft carriers to provide fighter support should it be required.

“The fleet flew an almost direct course for Kiel. It has been argued that Admiral Grimes should have made a devious approach. It has been argued that he should have waited for an overcast night. But the French semi-rigids could carry fuel sufficient only for the round trip, with no deviations. And, in those pre-radar days, the admiral had to see his targets-the Kiel Canal, the U-Boat pens, the Zeppelin sheds, The surface ships of the Royal Navy were supposed to have cleared the North Sea of all German vessels. But there were two German submarines at large-U27 and U33. Both of these vessels had surfaced to recharge their batteries. Both of them sighted the eastbound air armada. Both of them broke radio silence to report what they had seen, Admiral Strasser got his warning.

“Oh, I can envisage it . . .The hasty mustering of the flight crews and the ground crews, many of them called from their warm beds. There were married quarters at Kiel-and there must have been quite a few unmarried ladies who were giving comfort to the brave boys of the Luft-Marine. I can just see those airshipmen clambering aboard their Zeppelins, still buttoning up their trousers. I can see the big ships being walked out from their hangars, silvery in the moonlight. I can hear the splashing of the water ballast as they lifted. And there were the coloured signal lamps and the flickering of the searchlights as Morse messengers were flashed from ship to ground, from ship to ship, from ground to ship… And the throbbing of the engines and the shouts and, in the distance, the thudding of the antiaircraft guns, at Heligoland, as they opened up…”

“Anybody would think,” commented Duffin, “that you were there.”

“I wasn’t. Or wasn’t I? It all seems so vivid. There is German blood in the family, of course. A maternal grandmother. She could have been at Kiel. Anyhow, Strasser got his ships into the air. He launched his Taube fighters as soon as the Allied fleet was sighted, just crossing the coastline. They made for the leading ships-Deirdre, Kathleen, Fiona and Maeve, They got close, too close. After all a big airship, even without lights, is easy enough to see in bright moonlight. A small fighter plane is not. But once they opened fire, once they’d betrayed themselves, they’d had it. The Gatlings blew them to shreds. Not that the Pommy Camels, launched from the Royal Navy’s carriers, did much better against the Zeppelins, LZ40 was hit but not too badly. She lost gas but there was no fire. And LZ43 had somehow bungled the launch of her Taubes and so the fighters were airborne just in time to fight off the Royal Navy’s planes. They had not been expecting such opposition.

“Deirdre stood on, with her bomb-aiming officer peering into his sights, waiting for the first indications of canal locks, of U-Boat pens, of Zeppelin hangars. He must have been dazzled by the upward-stabbing searchlights, by the anti-aircraft shell bursts, although these latter were well short of their target. And I can just imagine that frosty-faced old bastard of an admiral, my great-grandfather, in his control cab, getting the situation reports from his officers -and growling, ‘Tell those bloody Frogs to close up! They aren’t much use but we can use their firepowerl’ (As a matter of fact the French Hotchkiss was a very effective air-to-air weapon but, like the Australian Gatling, it didn’t have the range.) And, ‘Why can’t the Poms send their aeroplanes where they’re needed? It’s the 70s they should be going after, not the old crocks!’

“Strasser kept out of range of the Australian Gatlings. His four 70s had climbed to the same altitude as my great-grandfather’s metalclads and then he had turned, running away (as it seemed) from the raiders. Soon Kiel would be spread out below the Allied airships, a helpless victim. At the same time the German air fleet was being slowly overtaken. The aeroplanes from both sides, the Camels and the Taubes, were still dogfighting but nobody, as far as I can gather from my reading of the various accounts of the battle, was worrying much about them. They were just nuisances, capable of drawing blood, just as a mosquito is, but no more than nuisances. This was an affair of big ships. It was the only airship battle in history-but, of course, nobody at the time knew that, Deirdre and Kathleen opened fire on LZ4O-crippled and lagging-with their belly Gatlings. This time there was a fire. She went down in a great flare of blazing hydrogen. And LZ38, too, had fallen astern of the main German fleet. She was just within Gatling range. There was another, slowly falling, funeral pyre.

“Meanwhile-according to Strasser’s own account of the action—his gunnery officers had their eyes glued to their rangefinders. The Gatling gun flashes enabled them to keep the pursuing ships in their sights. Too, there was the bright moonlight. Even so, it was not easy gunnery. Laying and training the big guns meant that the ships themselves had to be laid and trained. It was more like firing a torpedo from a submarine than an artillery piece from a surface vessel. But, at last, Deirdre was within range of the 88s. The four super-Zeppelins, the LZ7Os, made the necessary alterations to course and attitude so that all four stern guns could be brought to bear. They fired almost as one.

“According to the captain of the British R49, one of the few ships that returned from the raid, ‘One moment the Aussie flagship was there. And then she wasn’t. There was just a shower of burning wreckage. Then one of the other Aussies bought it. We flew through where she had been but came through with nothing worse than a few holes burned in the envelope. We were too busy hooking on our planes, pulling them in for refuelling and rearming, to worry much about it at the time…”

Duffin asked, “Are you sure that you weren’t there, Mr Grimes?”

“I’ve told you I wasn’t. But I’ve read all the accounts of the action-Australian, English, French and German. The Battle of Kiel was the airship action, with big ships slugging it out at relatively short range. The aeroplanes didn’t play much part after the first flurry; the hooking-on and launching procedures weren’t all that easy to carry out in the heat of battle. Things were different after the Americans put their flying drainpipes into the air, making the launching and recovery of fighter-bombers much easier, far less time.consuming. But at Kiel the flying drainpipes were still no more than an aeronautical engineer’s dream…”

‘You know your airships,” Duffin said.

“I should. Great-grandfather, the admiral, was one of the pioneers of lighter-than-air military aviation in Australia, in the world. I wonder what he would have said if, while he was second mate of that tramp windjammer which brought him here, somebody had told him what his end would be…”

Even as I spoke I was losing my hold on the here-and-now. I was no longer me, either of the late twentieth century mes. I was in a woman’s body and mind. It was a strange experience, a frightening one. The odd clothing, the nothingness where familiar organs should have - been, the top-heaviness about the chest … And was the mind that of my German grandmother? It must have been. I was cold and terrified, standing with others out in the street, deafened by the futile thunder of the anti-aircraft guns, by the explosions of the falling, earth-shaking bombs. I was looking up at the fire in the sky where the big ships were wallowing in their orgy of mutual destruction.

There was a burgeoning flower of flame far greater than any of the others had been. I knew, somehow, what it was. It must have been when R38, on fire but still under control, succeeded in putting herself alongside Dietrich’s LZ72.

“Wake up!” Duffin was saying irritably, “Wake up, Grimes!”

The spell was broken. I took the last piece of toast from the rack and helped myself to a liberal application of butter and marmalade.

“When you’ve quite finished,” said the major, “you’d bettor get ready for another session with the good doctor’s time-twister. Ned’s leaning on him and leaning on me, He wants that history written and finished by last Thursday at the very latest.”