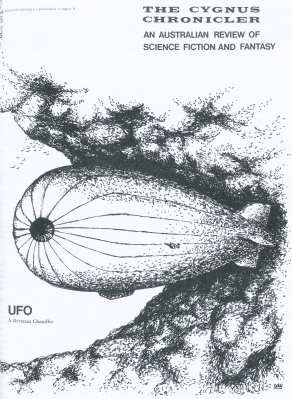

(Cover Michael Kumashov)

The Cygnus Chronicler - Dec 1979

Short Story

It was not good flying weather; if it had been any worse Captain Langeren would have decided to ride it out overnight at the mooring mast in the hope that the next day would show an improvement. He had made such decisions in the past. His owners hadn't liked it; neither had his passengers nor his crew. Come to that, he hadn't liked it himself. Ever since his appointment to command he had prided himself on his ability to maintain his timetable. The people of Alice Springs (he would say, at least half seriously) could set their watches as his ship passed overhead, whilst the citizens of Colombo could do the same as his nose made contact with the mooring cone. There would be more watch setting at Baghdad, Vienna and, finally, London.

He was a big man, Langeren - solid, apparently stolid, with a tanned, lined face under his thick grey hair that could have belonged to a farmer or a seaman as well as to an airshipman. It was the face of a man ever conscious of the vagaries of the weather, always on the alert for shifts of wind, always ready to counteract the effects of rain or snow. Rain, to him, had not been so much of a worry since the substitution of metal skins for the old fabric envelopes—but the accumulation of snow or ice could still cause a dangerous loss of buoyancy. Langeren looked out and down from his control-room viewports to the Harbour, to the great Bridge with its suspension cables stretched in a graceful catenary between the twin towers on either shore, the lights strung along their length lending an illusory aspect of frailty. Dusk, the captain thought, was the best time to see Sydney—the street lamps, just coining on, the harbourside apartment towers randomly illuminating their tier upon tier of windows. On an evening such as this the wind-driven grey veils of rain, the shifting, filmy translucence, added their own mystery.

The ship shuddered slightly as her turbines drove her north and west through the rising, moisture-laden wind. But she would be safe enough, thought Langeren, as long as there was no turbulence.

Lightning blazed in the murky sky ahead. 'Thank God for helium, sir,' said the Chief Officer, who had the watch. Langeren laughed. 'You'd be surprised if you knew how many of our own cloth argued against its use, saying that hydrogen has that much more lift. And then the same people screamed about fire hazard when we started putting heating coils in the helium gas cells…’ He looked around the familiar control room, at the tried and trusted instruments, at the two coxswains standing at their wheels, one watching the Gyro-compass repeater, the other the altimeter. There was nothing to worry about except the weather, and it would have to worsen considerably before his continual presence in Control was required. Too—as he well remembered from his own days as a watchkeeper—no officer likes to have the Old Man breathing down the back of his neck all the time.

He said, 'All being well, we shall be over The Alice at 0600 hours tomorrow. Pass the word to the Third and the Second to adjust revs as required. It's in the Night Orders. Call me, of course, if we're making too much leeway or if there's any sign of turbulence. Call me at five, in any case. I shall be making the usual circuits of Ayers Rock and Mount Olga after we've passed over Alice Springs.' He laughed. 'We have to give the customers their money's worth.'

'According to the met forecasts,' said the Chief Officer, 'there won't be much to see this time. The monsoon's set in good and proper.'

'We shall see what we shall see, Mister,' said Langeren.

He bade the watchkeepers goodnight and went aft to the observation lounge to have a few words with the passengers before retiring.

'Here's somebody who can bear me out!' cried the fat, florid man sitting at one of the tables with three companions. 'In all your years in the air, Captain, you must have seen a flying cross.'

'I'm sorry to have to disappoint you,' said Langeren, 'but UFOs have always avoided me.'

'But there are such things,' declared the scrawny, red-haired woman.

'All imagination,' stated the fat blonde.

'There may be something,' muttered her thin husband dubiously.

'There may be something,' agreed Langeren. 'On the other hand, there may not be.'

He extricated himself from the argument, made his rounds of the passengers, said his goodnights and retired to his sleeping cabin abaft the control room. He had no trouble getting to sleep. He trusted his ship and his officers. He trusted himself and knew that he would instantly awaken if there were any break in the rhythmic pattern of the creakings and rustlings of the great dirigible, if there were the slightest faltering in the hum of the powerful gas turbines.

* * *

He was called at 0500 hours. Some captains, he well knew, liked to be called about ten minutes or less before being required but he was not one of them. He appreciated the pot of tea brought to him by the night steward for his leisurely consumption, and after the initial cup there was the first pipe of the day. He showered then, and depilated, with ample time for the cream to take full effect. Finally, refreshed internally and externally, he dressed in a freshly laundered grey uniform and, at last, strolled forward to Control, entering the compartment at precisely 0550 hours.

The two coxswains were standing watchfully at their wheels, the Chief Officer, binoculars to his eyes, was peering forward through the rain-streaked glass of the viewport.

'Good morning, sir,' he grunted. 'If it is a good morning

It's the only one we've got,' said Langeren.

They'll be swimming in the Todd today!' said the Chief Officer.

Langeren chuckled, visualising the water swirling, through that usually dry riverbed. He joined his officer at the forward window, took his stance at the starboard clear view screen. He could see the sprawling township ahead, and the bright beacon lights atop the mooring masts of the airport. He had come in there often enough before he had graduated from the interstate to the overseas services; now, to him, it was just a milepost on the Sydney-London run. Nonetheless, he always exchanged salutations with the control officer as he passed over the city.

He hesitated before he left the view-port to go to the transceiver. That blackness right ahead was somehow ominous and the lightning rending it had been a cascade of blue fire. Yet it was the possibility of turbulence that worried him most.

'City of Ballarat to Alice,' he said into the microphone. 'Do you read me?'

'Loud and clear, Captain,' came the cheery reply. 'You're bang on time, as usual.'

'How are conditions west of you, Alice? Any turbulence?'

'No, Captain. This is just a dirty great rain depression. All the balloons launched from the stations have been going straight up, although they've had one helluva struggle against this downpour.'

'Thank you, Alice.' Then, to the Chief Officer, 'You can bring her round for the Rock, Mister.'

He heard the quiet order, the helmsman's response, the clicking of the gyro repeater. As he turned away from the transceiver lightning blazed about the ship and brush discharge flared and crackled from every metal fitting in the control room. His heart almost stopped as he felt the ... wrench (?). He thought, God! She's breaking up!'

But she was not, he realised. He should have felt relief, but the dread, the somehow irrational dread persisted. She was sliding through chaotic darkness at an impossible angle, through and across the normal dimensions of Space. And of Time? Beyond the control room windows was a swirling nothingness, an emptiness that, briefly, was not empty.

The Chief Officer shouted. The altitude coxswain screamed. The helmsman swung his wheel hard over and the ship complained in every structural member. She was too big, too long to submit to a violent alteration of course without protest.

Lightning blazed again - and suddenly, there through the viewports, was the familiar scene of the sprawling city with, on the hill, the skeletal shapes of the mooring masts, each tipped with its bright beacon light.

'City of Ballarat!' came the frightened voice of the controller. 'What happened? You ... vanished . . .'

'Sir!' demanded the Chief Officer.

'Did you see it? A flying cross! I thought, it was going to hit us!'

'Yes, I did see it,' admitted Langeren slowly. 'A UFO. A flying cross. I know that it sounds crazy - but it looked like the pictures I've seen of those old heavier-than-air flying machines that those American brothers—Ryde or Reid or some name like that—were playing with years ago. But they never got properly off the ground . . .'

* * *

White-faced, the Captain of the Fokker Friendship stared at his First Officer. The First Officer, equally pallid, stared back.

'It's bad enough having to fly in this weather,' said the Captain at last, 'with- out being as near as dammit rammed by flying saucers...

'It looked almost like an airship said the First Officer diffidently. 'Sort of like the Hindenburg, or one of them. And there was some kind of badge painted on its nose . . . It could have been the Qantas flying kangaroo . . .'

The Captain managed a shaky laugh. And I thought that I was seeing things. A Qantas airship! I'd sooner believe in flying saucers. Airships never were and never will be any good.'